A few months back, I wrote about the process of recipe keeping and my own family’s generational traditions. Here is a sequel—or more accurately a prequel—to that story.

If you are triggered by talk of clutter, piles, and moldering papers, then this post might not be for you. But if you’re intrigued—as I am—by family mysteries, heirlooms, and very old recipes, then read on.

On a recent Sunday, I stopped in to see my aunt Katie & uncle Andy in Maryland, and as Katie often does she had an armload of mystery treasures for me, along with some homemade pesto and iris rhizomes for me to plant in our Brooklyn garden.

The pile, which had belonged to my grandmother “Mimi” (who was a food writer), filled up an empty wine case. The contents included travel souvenirs, a bunch of well-worn and annotated cookbooks Mimi had used in the mid-20th century, and my grandfather’s 1924 Fresno High yearbook, which was plastered with multiple newspaper clippings announcing his expulsion from school—these seemed kind of proudly displayed, if you ask me (he eventually went on to graduate and become a mostly upstanding citizen).

one person’s trash…

As we were going through the books, Katie pointed out a tobacco-colored notebook that was in particularly rough shape and commented “this one looks really old but I have no idea what it is.” She gingerly turned the handwritten pages inside, many of which were loose and deeply yellowed. There were clippings and shreds of paper hanging on by rusted pins and in some cases sewed onto the notebook’s paper with thread. We speculated on whether it had been mice or time that had nibbled away at the edges of the papers, rendering them lacy and delicate. I was immediately smitten.

It was clear to me that this homespun book was from before my grandmother’s time, but when? Whose? After I got it home, it took a couple of hours of toggling between the notebook’s pages and my ancestry.com tree to connect the dots. Later, through the wondrous ways of the internet, I was connected with Don, the owner of Rabelais Inc. in Maine (a culinary bookshop I now can’t wait to visit), who as it turned out was the perfect person to help me contextualize this collection and suggest ways to preserve it.

Evidence points to the fact that the notebook was mainly used by Bettie Wheat Anderson, my great-great grandmother, who lived from 1832-1905 in Richmond, Virginia. Notebooks of this type would have been a family’s primary catalog of recipes, whether the person doing the cooking was the woman of the house or a domestic servant (or both). Since folks back then were generally less wasteful with their paper, many of the recipes are scribbled on the flip side of letter drafts, doodles, old bits of accounting; these “B sides” are fascinating in their own right. Some bear dates, which helped me deduce that most of the activity in the notebook took place between the 1870’s and the 1890’s. Adding another layer, the many different penmanship styles and ink qualities found in the book indicate different time periods and multiple authors. Clearly, there was a lot of passing along of recipes, swapping, and mailing them. A few are attributed to “M.D. Anderson”, who I’m pretty sure was my great-great-great-grandmother Maria (1803-1879)—the mother-in-law of Bettie—passing along her wisdom to the next generation.

Damsons are a small, sour variety of plum that were commonly grown and preserved in England and early U.S./colonies, but they’re harder to find now.

Most of the “receipts” in the book are for preserved foods, like pickles and salt-cured meat, or baked items such as cakes. Don at Rabelais explained to me that such content was typical in these home cookbook compilations, as baking and preserving required more precision, whereas cooked vegetables and roasted meats were more intuitive. Lest you think cooking was bland back then, many of these foods were highly spiced; ginger, allspice, cloves, and peppers all appeared frequently. You can find similar flavor profiles in Mary Randolph’s 1824 iconic cookbook The Virginia House-Wife.

Among the desserts in my family’s notebook is something called a Democrat Cake (“election cakes” were popular in the 19th century), and some cornmeal-based recipes—corn being a staple ingredient in Virginia since well before the arrival of European settlers. In the recipe below for “Excellent corn bread", note the use of the “long s” where double ss appeared, so “thickness” looks sort of like “thicknefs”. This appears in some of the papers but not all, as the long s faded from fashion some time during the 19th century, depending on factors like region and the age of the writer (Bettie Anderson did not seem to use the long s—this was someone else’s handwriting). Notice, also, that the cooking instruction for the cornbread says, simply, “bake quickly”—since electric ovens had not come into use, and baking was an imprecise endeavor. My own go-to cornbread recipe by Edna Lewis calls for 450°, which I’d say amounts to a pretty quick bake. A “slow oven,” used for things like delicate cakes, might translate to 350°.

There are plenty of newspaper clippings fastened into the pages or floating loose: A notice of the auctioning of an Anderson family property and its mill. A poem entitled “His Grandmother’s Mince Pie.” A rundown of “New York Fashion Notes” from January 9, 1876, which informs the reader that “Grecian coils are going out of style and the long braided loop is returning to favor. Long curls at the back of the neck are now the style for evening dress.”

Victorian chic

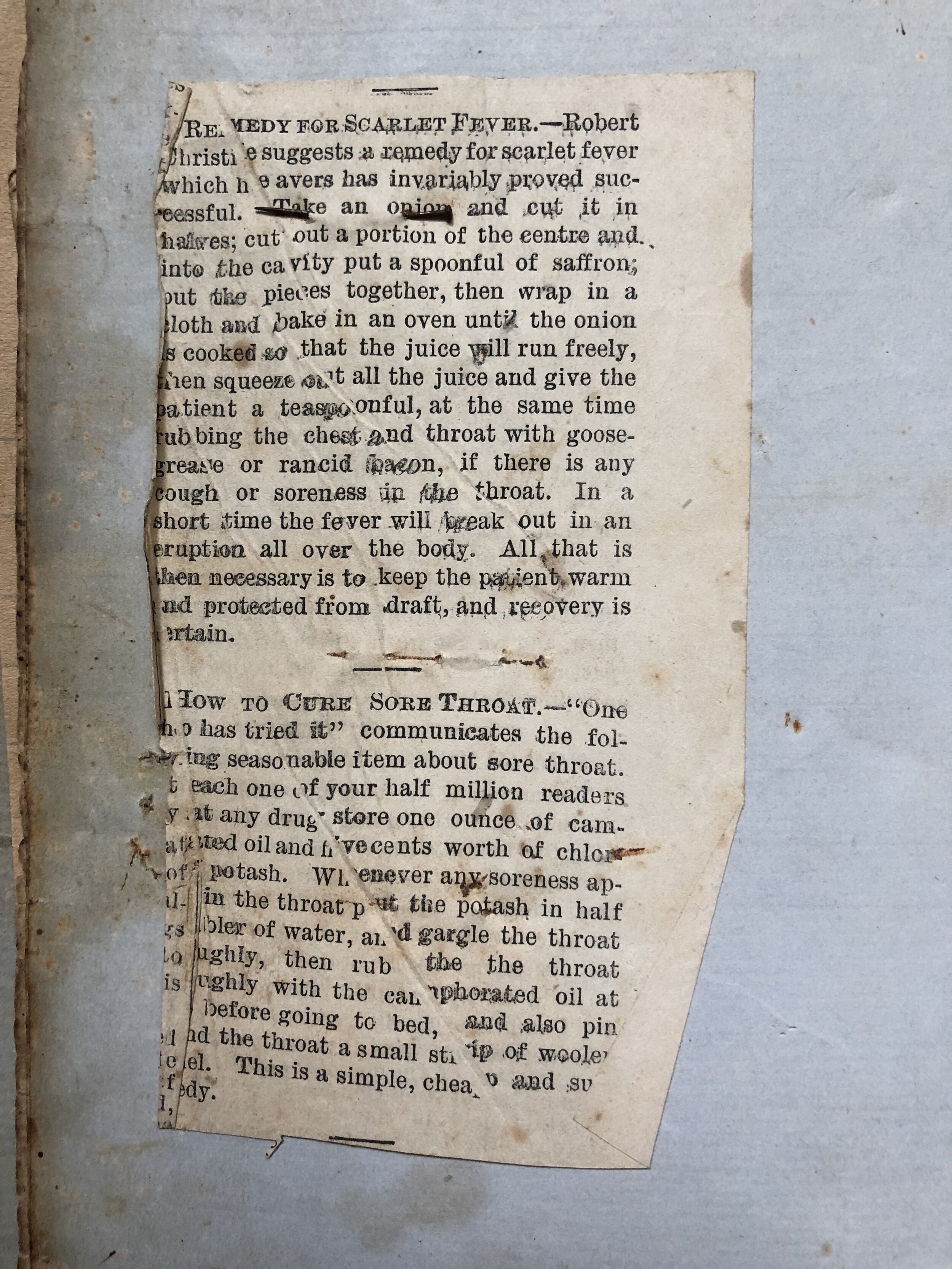

Numerous home remedies and homespun medical advice pinned into the book hint at ailments that constantly plagued families of that era, but which we rarely give a thought nowadays. The clipped and saved remedies for Smallpox, Scarlet Fever and consumption sound a little dodgy now (goose grease and rancid bacon, anyone?)…but considering some of the remedies that have been attempted during our current pandemic, it’s nice to know that some things never change.

Don’t try this at home

So what do all these clippings and handwritten articles add up to? They’re just a heap of crumbling papers from the past, yes, but the fact that they have survived down through at least five generations of my family feels nothing short of miraculous. Many hands wrote those recipes, and the little pieces tucked in among the pages reveal multitudes about the dailiness of my ancestors’ lives. My grandmother had this notebook in her possession for a stretch, and some of the recipes bear her own initials and her familiar scrawl that says “copied” (I’ve found the copies in her recipe tins). She had a fascination for culinary history, which I inherited along with the material things she saw fit to save. As I look through all of these pages and make sense of them I imagine her doing the same, and time seems to compress in a way that is both dizzying and comforting. Could the creators of these notes have imagined their writings would be read by their descendant 150 years later, into an age when foods from every corner of the globe reach people via metal flying machines, and recipes are searched and saved on pocket-sized electronic devices that seem glued to everyone’s palms?

An object like this is both common and rare. Common, because every family probably had one—yours likely did, too, even if they lived in a different country. Rare, because how many families are crazy—or lucky—enough to hold onto something like this? I know I’m damaging the pages a little bit each time I flip through and tiny flakes slough off like dandruff, but I’ll preserve this precious thing the best I can, look through it from time to time, and encourage my children to do the same. A notebook like this was, after all, meant to be used.

A blackberry cordial receipt and a child’s doodle